Sweet Old Orientalism

During the XIX century, an occidental artistic movement called Orientalism reached a peak and had an impact on various creative spheres, from architecture to painting, litterature and music. This month, King and Country announced a figure that can be considered as a tribute to XIX century orientalism: the AE079 - The Egyptian Harpist.

Orientalism’s true beginning is hard to locate. But it’s really during the XIX century that this artistic movement truly exploded. When Napoleon campaigned in Egypt from 1798 to 1801, artists were brought in the expedition to visually document archeological finds. In Europe, those illustrations fueled the collective imagination with visions of an outlandish country waiting to be rediscovered. This first wave of egyptomany was only the first step in the XIX century orientalism. Eventually, colonialist politics from other European countries extended the global fascination to the Maghreb and Middle East countries. People in occident, unable to properly understand what those countries were, appropriated them with their creativity. They started to dream of exotic landscapes, ancient times, dangerous beasts, powerful kings, ferocious warriors and sensual women. Therefore, orientalism is known to be frequently inaccurate and can be sometimes closer to Dungeons and Dragons than reality.

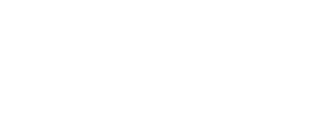

The 1798 Egyptian Expedition Under the Command of Bonaparte (1835) by Léon Cogniet

The artwork of interest today is The Egyptian Signer, created by the English sculptor Edward Onslow Ford (1852-1901) in 1889. This bronze represents a signing Egyptian woman. She is depicted in a very academic contrapposto pose. Her opened mouth evoques the sound of her voice signing. She is also standing on a small cubic stool. With her right hand, she holds a giant and highly decorated harp. Such massive harps are accurate and were found on paintings and in tombs.

The Egyptian Signer (1889) by Edward Onslow Ford

The piece by King and Country is a splendid adaptation of this bronze. Almost every feature from the original work of art were kept, including the nice contrapposto pose. In fact, this figure can almost be considered as a painted and reduced version of the original bronze. However, one major change was done: a loincloth was added.

Some people might argue that the Ancient Egypt collection includes too much nudity, but King and Country is actually adjusting the collection to modern standards. Nudity in Ancient Egypt was not taboo as it is today and many depictions from that time as written documents prove it. Nudity was in fact the norm when it came to female performers, poors, servants, slaves and children. Most of the adults were wearing simple clothings, but it was still optional under certain circumstances such as fishing and labouring. Fancy clothings were only used by the upper class and still many were made of semi-transparent fabrics. So King and Country is actually doing a good compromise between historical accuracy and modern standards where nudity is often seen as objectification of the individuals.

Detail from Tomb of Nebamun, c. 1350 B.C.

Today, XIX century orientalism is sometimes perceived as racist. Many artwork in that genre depicts peoples in savage states, with barbaric behaviors and no morality. But not all the orientalist art works were done to diminish orient people. In most of the cases, it came from a genuine fascination toward those people and the will to discover other worlds. And this interest in other cultures, despite being poorly done, was still a first step toward understanding them properly. So orientalism is a genre to appreciate for what it did right, while keeping in mind that it was a different time. In that context, the figure of the Egyptian Harpist by King and Country is doing a wonderful job. It goes beyond a representation of a Harpist. Because without orientalist arworks from the XIX century such as The Egyptian Signer by Onslow Ford, there would be no collection of Ancient Egypt by King and Country today.

Français

Français